Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), the most common inherited cardiomyopathy, is characterized by LVH (wall thickness in any segment ≥ 1.5 cm) without a secondary cause. It exhibits variable phenotypic expression due to incomplete penetrance. This condition leads to a range of symptoms, from asymptomatic to heart failure and Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD).

-

Formal definition: “A clinical diagnosis of HCM in adult patients can therefore be established by imaging, typically with 2D echocardiography or cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) showing a maximal end-diastolic wall thickness of ≥ 15 mm anywhere in the left ventricle, in the absence of another cause of hypertrophy in adults.” 1

- 📝More limited hypertrophy (13-14 mm) can be diagnostic when present in family members of a patient with HCM or in conjunction with a positive genetic test identifying a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant often in a sarcomere gene.

-

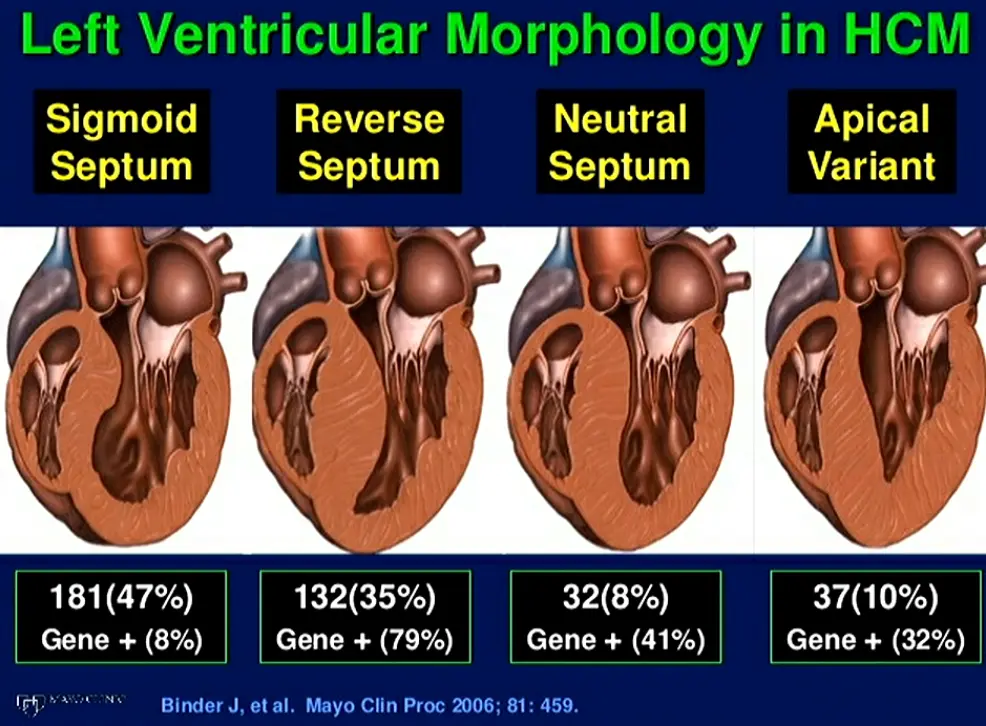

Nearly any pattern and distribution of LV wall thickening can be observed in HCM, with the basal anterior septum in continuity with the anterior free wall the most common location for LVH. In a subset of patients, hypertrophy can be limited and focal, confined to only 1 or 2 LV segments with normal LV mass.

-

TODO

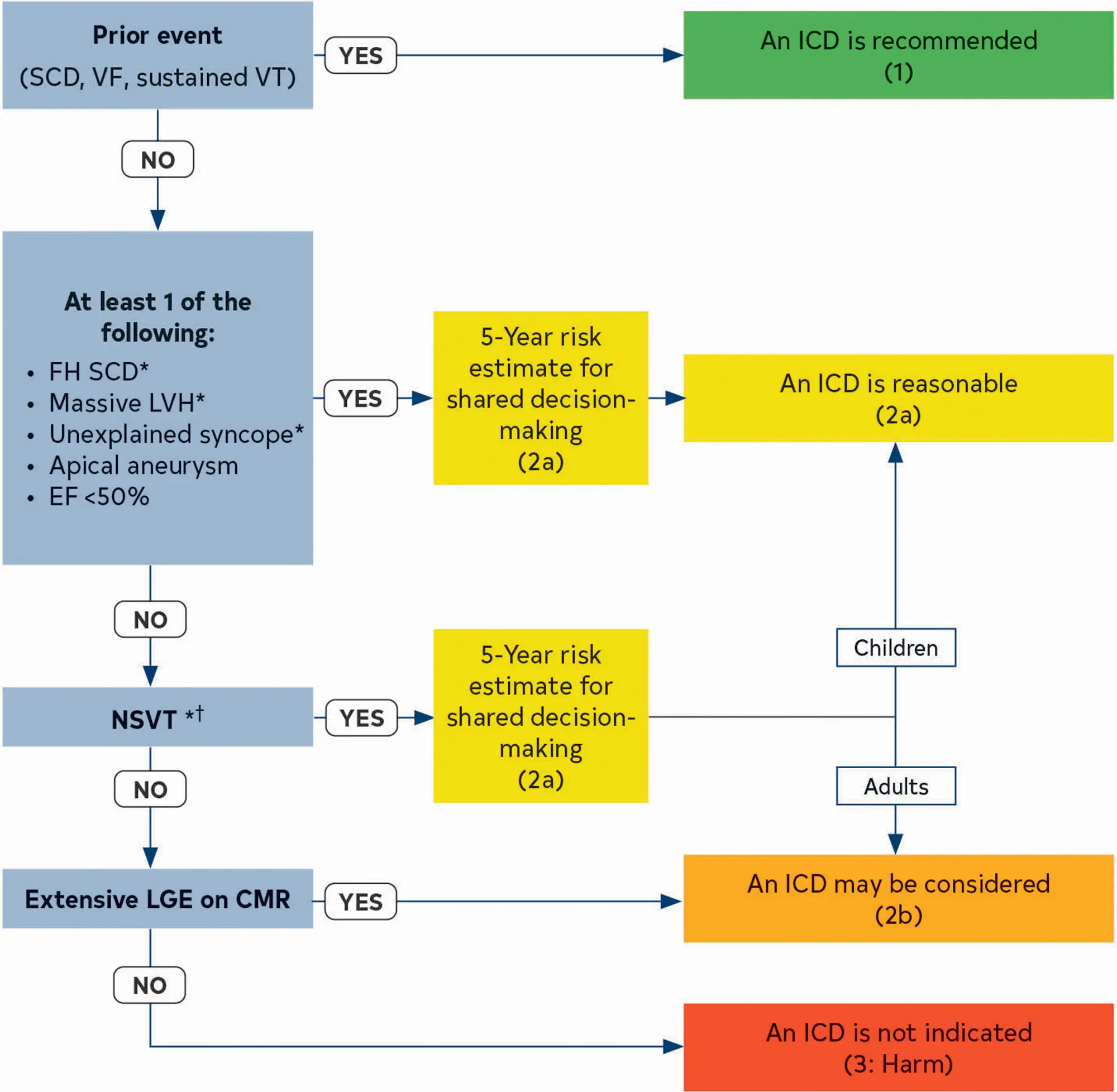

- Risk factors that if present may warrant ICD implantation:

- ≥15% LGE

- Frequent NSVT

- Risk factors that if present may warrant ICD implantation:

Pathophysiology

- Arises from enhanced actin-myosin interaction results in excessive myocardial contraction and simultaneous impairment in diastolic relaxation.2

- The pathophysiology of HCM consists of dynamic LVOT obstruction, mitral regurgitation (MR), diastolic dysfunction, myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias, metabolic and energetic abnormalities, and potentially autonomic dysfunction.1

HCM’s hallmark is the dynamic LVOT obstruction, which can occur at rest (1/3 of patients) or with provocation in 75% of HCM patients.2 Unlike aortic stenosis, where the obstruction is fixed, the degree of blockage in HCM changes based on factors like heart rate, blood volume, and even body position. This obstruction occurs due to the thickening of the ventricular septum, which protrudes into the LVOT, particularly during systole. Of note, while LVH is most frequently asymmetric, involving the ventricular septum, but can occur in any pattern.2 This encroachment, coupled with systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve leaflet, restricts blood flow out of the ventricle.

Not all HCM is 'obstructive'

~1/3 of patients with HCM are non-obstructive 2

- Obstruction Phenotypes: 2

- dynamic LVOT obstruction

- midventricular obstruction (MVO)

- an important subtype of HCM to recognize as it may result in refractory symptoms and be associated with an increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias, mortality, and LV aneurysm (apical aneurysms often?) with or without thrombus.

- usually related to hyperkinesia of the mid-LV cavity → apposition of hypertrophied mid-septum and hypertrophied papillary muscles

- Color-flow Doppler shows turbulence at mid-ventricular level

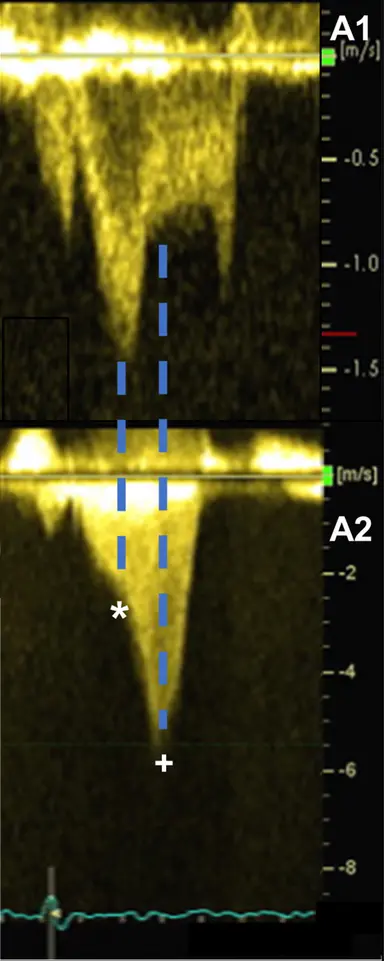

- CWD typically shows a narrow, late-peaking systolic velocity (“ice pick” appearance)

- combined LVOT and MVO

This dynamic obstruction results in:

- Increased LVOT velocity and gradient: The heart works harder to eject blood, leading to a pressure difference (gradient) across the narrowed LVOT.

- Mitral Valve Issues are relatively common and include hypertrophy or displacement of the papillary muscles, abnormal attachment of the chordae tendinea with excessive anterior positioning, and elongation of the anterior mitral leaflet.2

- Mitral Regurgitation SAM can cause the mitral valve to malfunction, allowing blood to leak back into the left atrium.

- SAM of the mitral valve is a key feature of HCM. It occurs when the mitral valve leaflet, due to the altered blood flow dynamics, gets pulled towards the thickened septum during the heart’s contraction (systole). This further exacerbates the obstruction and can lead to mitral regurgitation.

- Mitral Regurgitation SAM can cause the mitral valve to malfunction, allowing blood to leak back into the left atrium.

- Myocardial ischemia: The thickened heart muscle demands more oxygen, while the obstructed coronary arteries struggle to deliver sufficient blood flow.

- The thickened muscle needs more oxygen, but the narrowed coronary arteries can’t deliver enough, leading to ischemia (lack of oxygen). This ischemia further worsens the heart’s ability to relax, increasing pressure and perpetuating the cycle.

- Diastolic dysfunction: The stiff ventricle struggles to relax and fill with blood properly.

Symptoms

HCM symptoms arise from the interplay of LVOT obstruction, MR, myocardial ischemia, and diastolic dysfunction. These symptoms often fluctuate in intensity due to the dynamic nature of LVOT obstruction. Common symptoms include the classic triad of dyspnea, angina, syncope. The fluctuating nature of LVOT obstruction in HCM translates to these symptoms appearing and disappearing based on various triggers.

Diagnosis

- Diagnosis of exclusion

- ⚠️ things like dynamic LVOT obstruction and SAM are suggestive of HCM, but not pathognomic

- Diagnosing HCM involves ruling out other conditions that cause LVH, such as hypertension, aortic stenosis, or infiltrative diseases like amyloidosis.

- Phenocopies span 2

- physiologic LVH such as athlete’s heart

- although LVH is usually symmetrical, rarely exceeds 1.4 cm, and does not typically result in SAM or LVOTO

- pressure LVH d/t ↑ afterload

- hypertensive heart disease

- could have SAM and/or LVOTO d/t septal bulge, especially if hypertension is severe, long-standing, and untreated

- 🔍 “pseudo” SAM, which is the occurrence of SAM at end-systole, is suggestive of hypertensive heart disease. By contrast, SAM in HCM occurs in early systole (hypertrophied septum redirects early low-velocity systolic flow below the MV and displaces it anteriorly)

- fixed subaortic stenosis

- valvular aortic stenosis

- supra-aortic membrane

- hypertensive heart disease

- storage disorders such as Fabry cardiomyopathy

- infiltrative disease most commonly in the form of cardiac amyloidosis.

- physiologic LVH such as athlete’s heart

- 📝 overlapping conditions is possible, especially with systemic hypertension in HCM, which is present in nearly half of some large cohorts.2

- Wall thickness ≥ 1.5 cm on Echo, CT, or MRI in the absence of another cause points to HCM

- Genetic Testing

- While HCM is a genetic disease, genetic testing isn’t always necessary for diagnosis. Genetic testing helps identify specific gene mutations, which can be helpful for family screening but doesn’t change the initial approach to management.

HCM Mimics

- Systemic disorders include various metabolic and multiorgan syndromes such as RASopathies (variants in several genes involved in RAS-MAPK signaling); mitochondrial myopathies; glycogen and lysosomal storage diseases in children; and Fabry, amyloid, sarcoid, and Danon cardiomyopathies.

- In these syndromic or infiltrative diseases, although the magnitude and distribution of increased LV wall thickness can be similar to that of HCM, the pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for hypertrophy, natural history, and treatment strategies are not the same.

- Causes of secondary LVH, which can also overlap phenotypically with HCM, including remodeling secondary to athletic training (ie, ‘athlete’s heart’) as well as morphologic changes related to long-standing systemic hypertension (ie, hypertensive cardiomyopathy). Similarly, hemodynamic obstruction caused by left-sided obstructive lesions (valvular or subvalvular stenosis) or obstruction after antero-apical infarction and stress cardiomyopathy can cause diagnostic dilemmas.

- Although HCM cannot be definitely excluded in such situations, a number of clinical markers and testing strategies can be used to help differentiate between HCM and conditions of physiologic LVH.

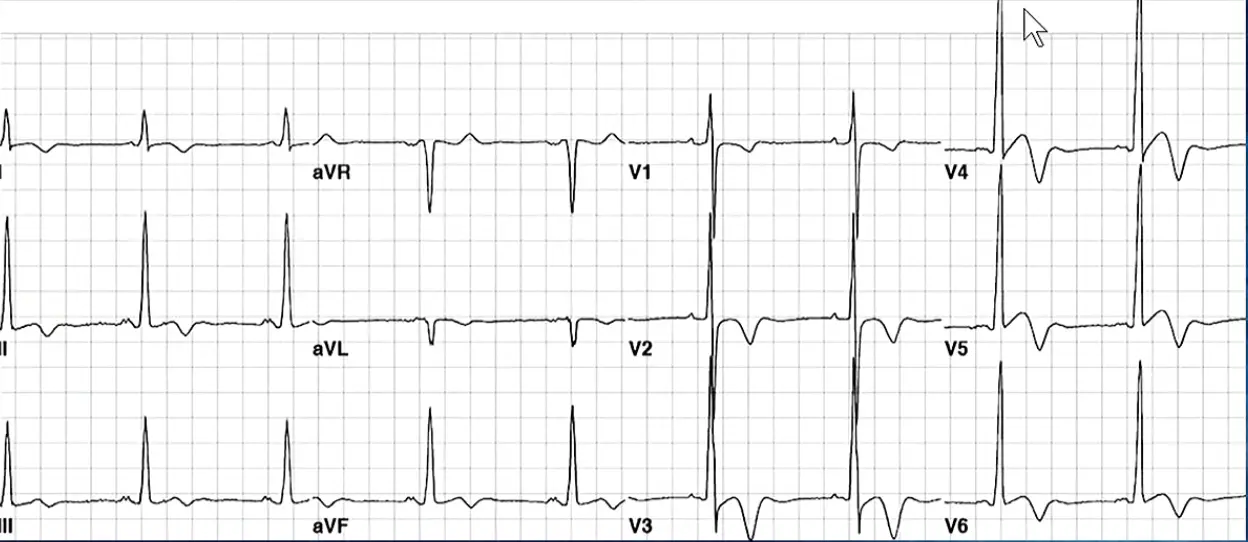

ECG

- Yamaguchi - should raise suspicion for apical HCM

Echo in HCM

SAM and dynamic LVOT obstruction are non-specific

Things like dynamic LVOT obstruction and SAM are suggestive of HCM, but not pathognomic

- LV wall thickness

- Systolic anterior motion (SAM)

- Several morphologic abnormalities are also not diagnostic of HCM but can be part of the phenotypic expression of the disease, including hypertrophied and apically displaced papillary muscles, myocardial crypts, anomalous insertion of the papillary muscle directly in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve (in the absence of chordae tendineae), elongated mitral valve leaflets, myocardial bridging, and right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy.

Systolic anterior motion (SAM)

- Although common in HCM, SAM of the mitral valve and hyperdynamic LV function are not pathognomonic and are not required for a clinical diagnosis.

LVOT Obstruction

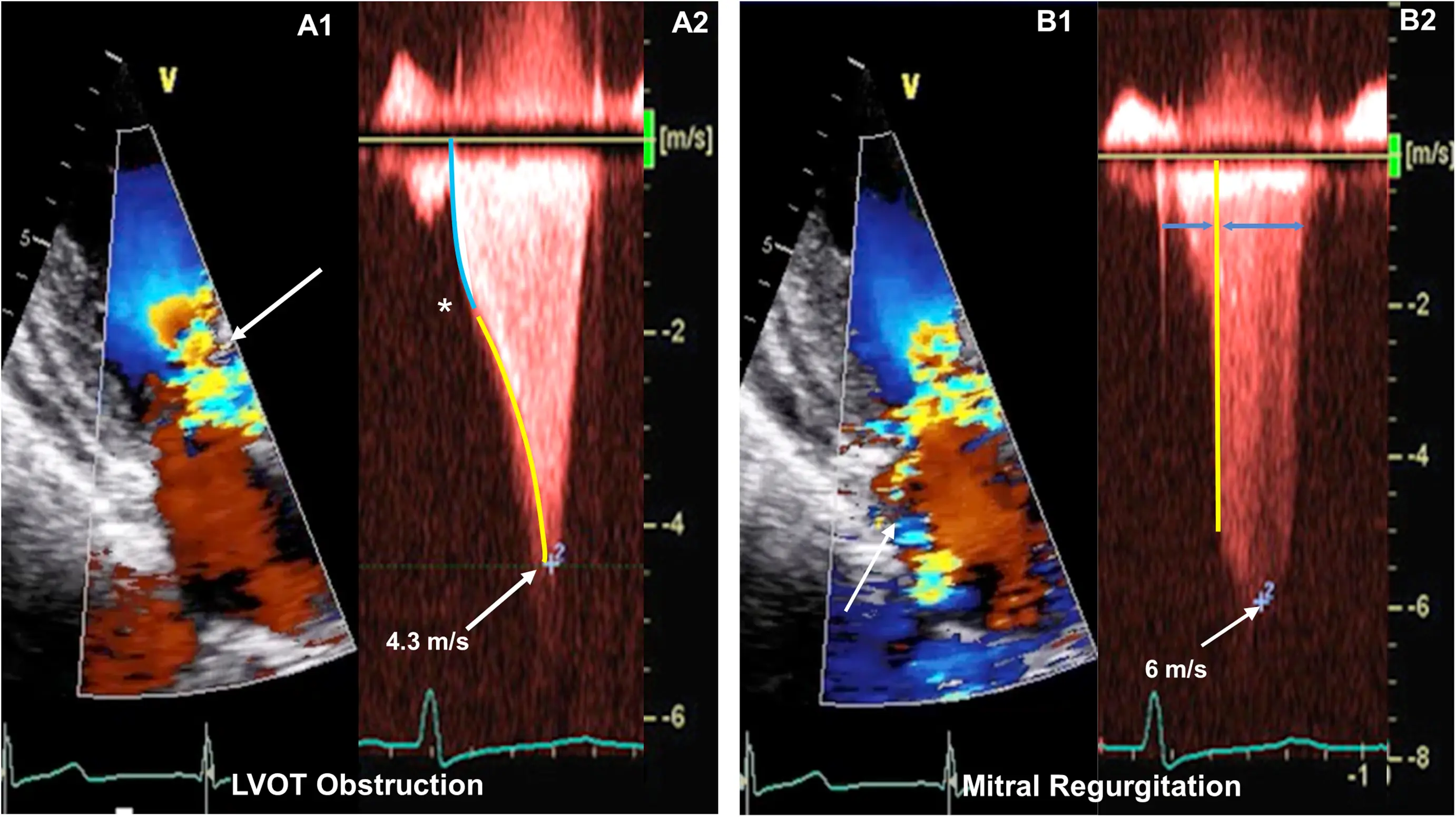

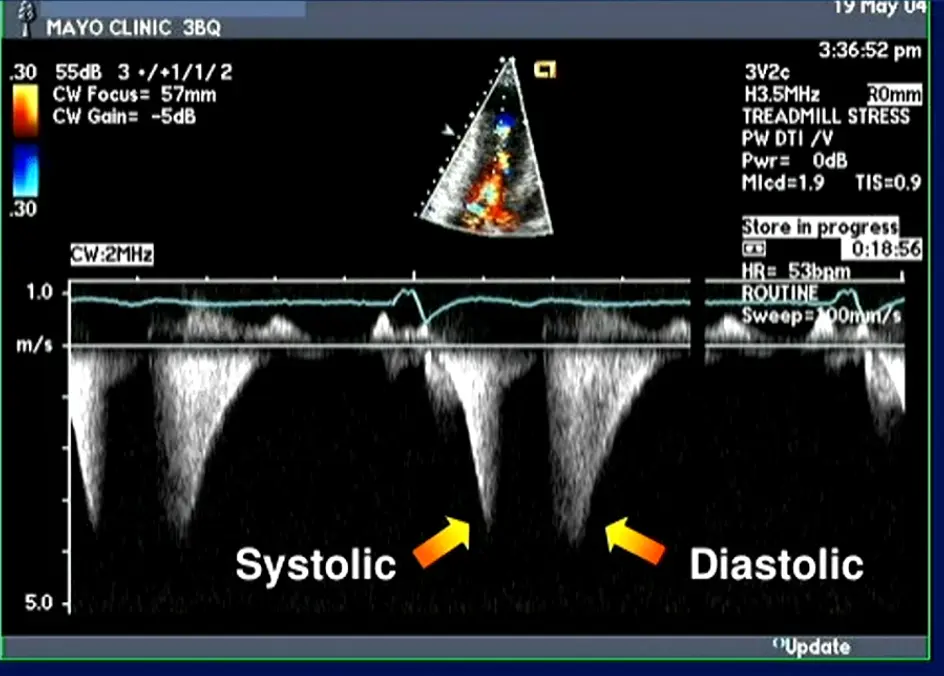

The degree of resting LVOT obstruction has been shown to be directly proportional to the degree of MR associated with SAM.2

-

Primarily caused by SAM of the mitral valve

-

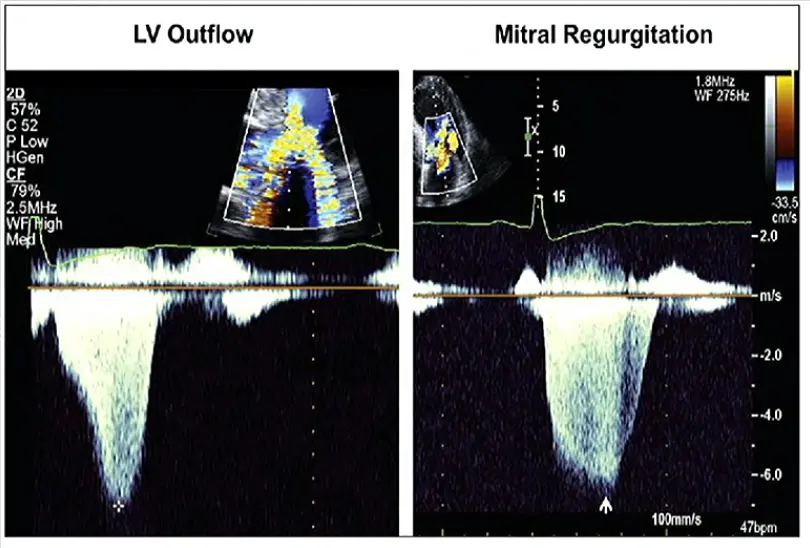

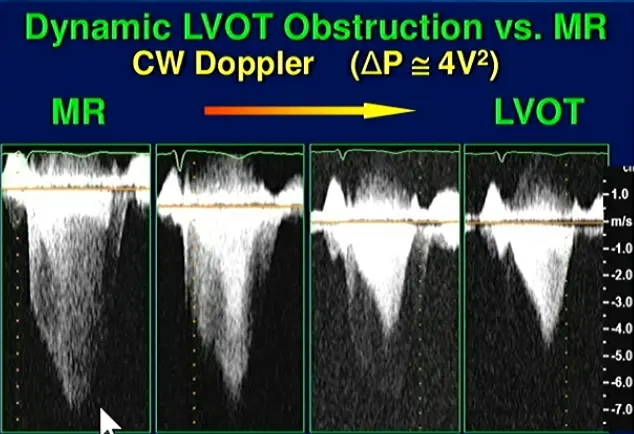

LVOT obstruction is assessed using Continuous Wave Doppler-derived peak instantaneous gradient

-

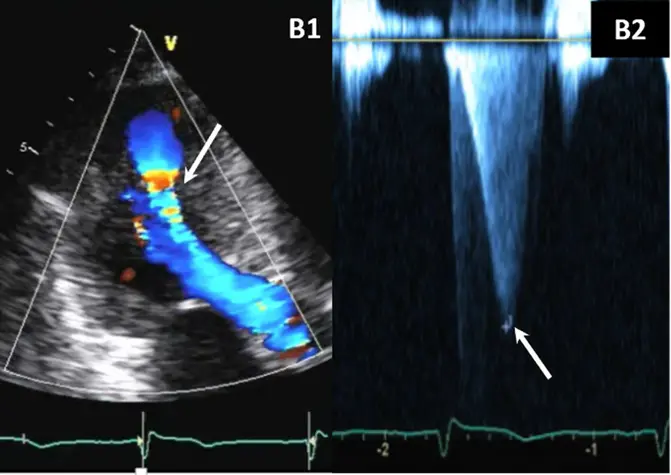

⚠️ Make sure you are not getting the MR jet. Easy to happen b/c the MR jet is right next door to the LVOTO.

- MR jet is more rounded

- MR jet is more rounded

-

📝 Can occur even in the absence of LVH 2/2 anatomical issues of the MV leaflet and papillary muscles‼️

-

Obstruction is considered present if peak LVOT gradient is ≥ 30 mm Hg. Resting or provoked gradients ≥ 50 mm Hg are generally considered capable of causing symptoms and, therefore, are the threshold for contemplating advanced pharmacological or invasive therapies if symptoms are refractory to standard management.1

- LVOT gradient ≥ 50 mm Hg (at rest or with provocation) identifies severe obstruction and often serves as a threshold for pursuing septal reduction therapy or initiation of myosin inhibitor therapy.

- Provocative measures include standing, Valsalva strain, or exercise with simultaneous auscultation or echocardiography.1

-

Classification of HCM on the basis of obstruction: 2

- resting obstruction (LVOT gradient ≥30 mm Hg),

- latent obstruction (<30 mm Hg at rest, ≥30 mm Hg with provocation), and

- nonobstructive (<30 mm Hg at rest and with provocation).

-

⚠️ LVOTO in HCM is dynamic and sensitive to ventricular preload, afterload, and contractility. 2 Thus, gradients vary with heart rate, blood pressure, volume status, activity, medications, food, and alcohol intake.

-

Classically described as having a “dagger”-shaped appearance, but honestly resembles more of a nonworking upper edge of a Bowie knife. 2 Dr. Saghir also used the term “dragon’s tooth,” which I like.

-

Gradients > 60 mmHg may take on a “lobster claw” pattern 2

-

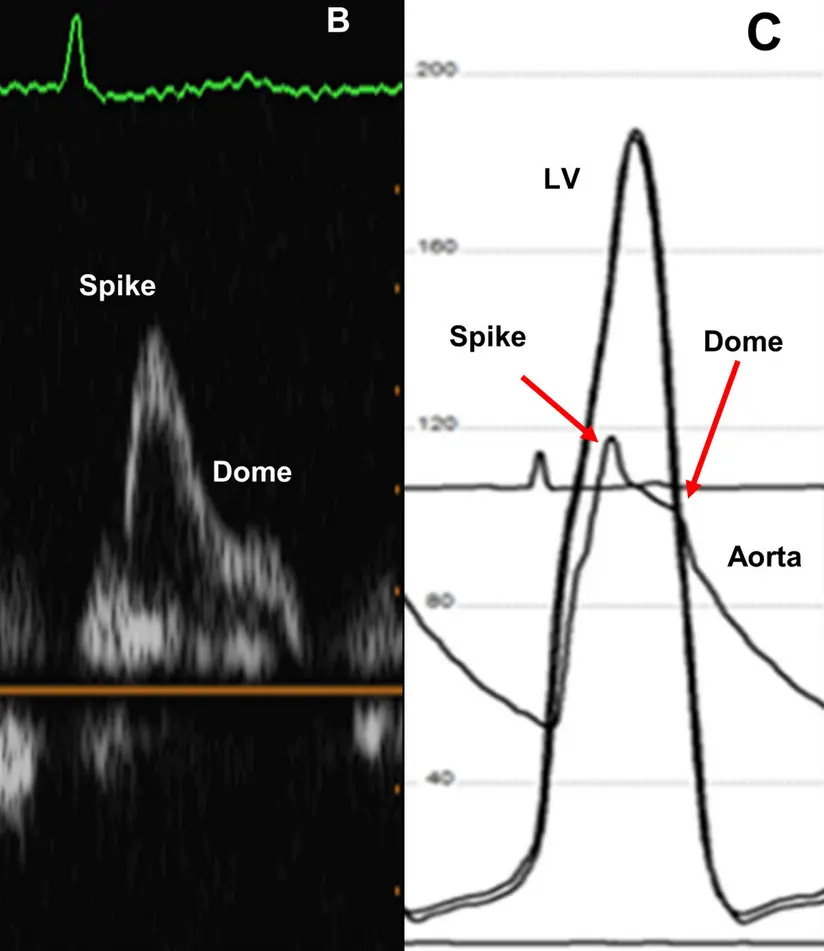

Pulsed Wave Doppler of the thoracic aorta

- Double-peaked, “spike-and-dome” pattern

-

Aortic pressure tracing will also feature the “spike-and-dome” pattern

LVOT Gradient

- Calculate LVOT gradient using the peak velocity using the simplified Bernoulli equation

- Calculate LVOT gradient using the MR velocity

For example, MR peak velocity 8 m/s, estimated LAP 15 mmHg, SBP 98 mmHg

We can then use this value to quantify the LVOT gradient

Mitral Regurgitation

- MR in HCM can be either primary or secondary (d/t SAM)

- Common primary abnormalities of the mitral valve in patients with HCM include excessive leaflet length, anomalous papillary muscle insertion, and anteriorly displaced papillary muscles.1

- MR jet characteristics can be useful to tease out if 1˚ or 2˚ MR

- MR caused by SAM is typically mid-to-late systolic in timing and posterior or lateral in orientation, owing to the anterior distortion of the mitral valve and compromised leaflet coaptation.1

- 📝 central and anterior jets may also result from SAM of the mitral valve.

- MR caused by SAM is typically mid-to-late systolic in timing and posterior or lateral in orientation, owing to the anterior distortion of the mitral valve and compromised leaflet coaptation.1

- If anterior/centrally directed jet, then maybe it isn’t just the SAM that’s the problem

- Posteriorly-directed MR jet (classically): Usually, the anterior and posterior MV leaflets fail to coapt in mid-late systole, due to the upward and anterior motion of the anterior leaflet toward the LVOT, creating a funnel that directs the MR posteriorly through the interleaflet gap.2

- Contours compared to SAM:

- Phenylephrine provocation may be of benefit because it increases afterload, which attenuates SAM-related MR but not primary MR.2

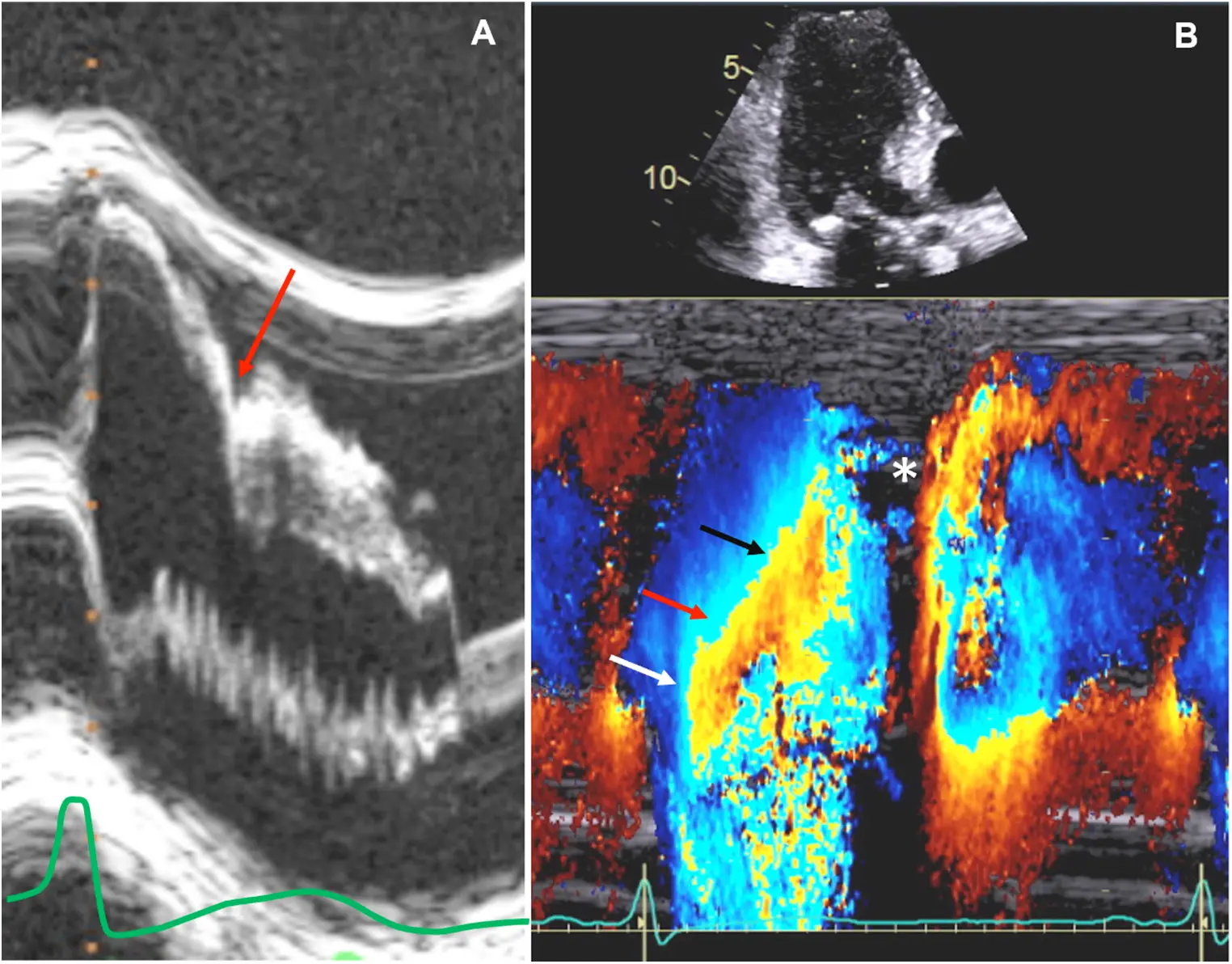

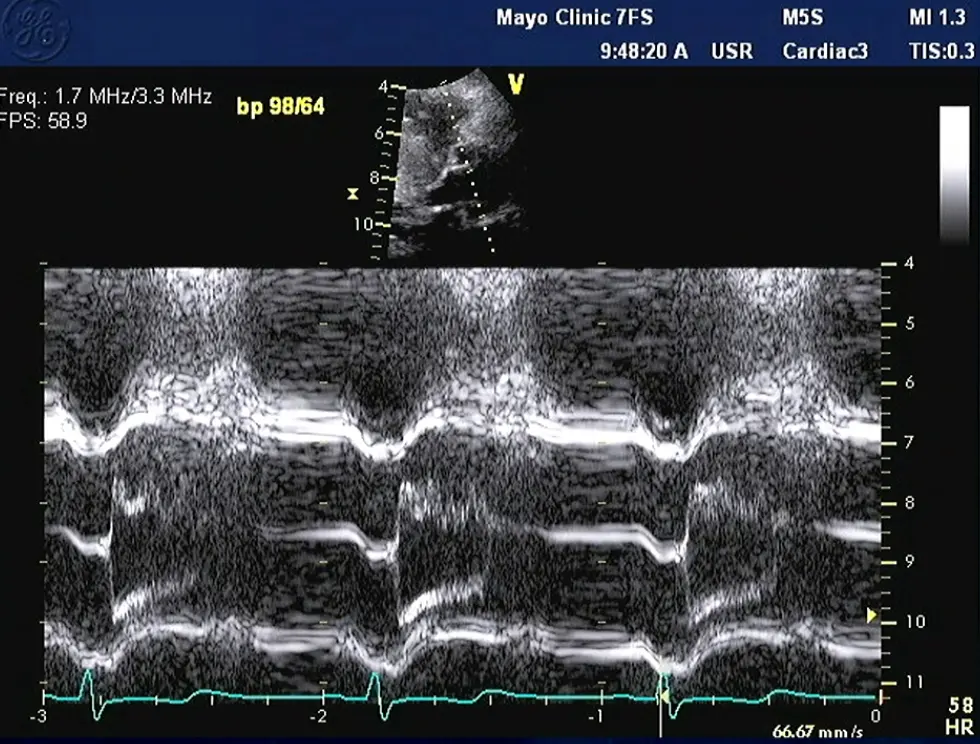

M-mode

- Temporal resolution of M-mode → the duration of SAM where it is in contact with the septum correlates w/ severity of LVOT obstruction

- M-mode in the parasternal long-axis view may assess for midsystolic notching of the aortic valve, reflecting very rapid ejection of LV stroke volume in early systole followed by attenuation of stroke volume in the obstructive phase.

Notice the turbulence, which suggests LVOTO

Notice the turbulence, which suggests LVOTO

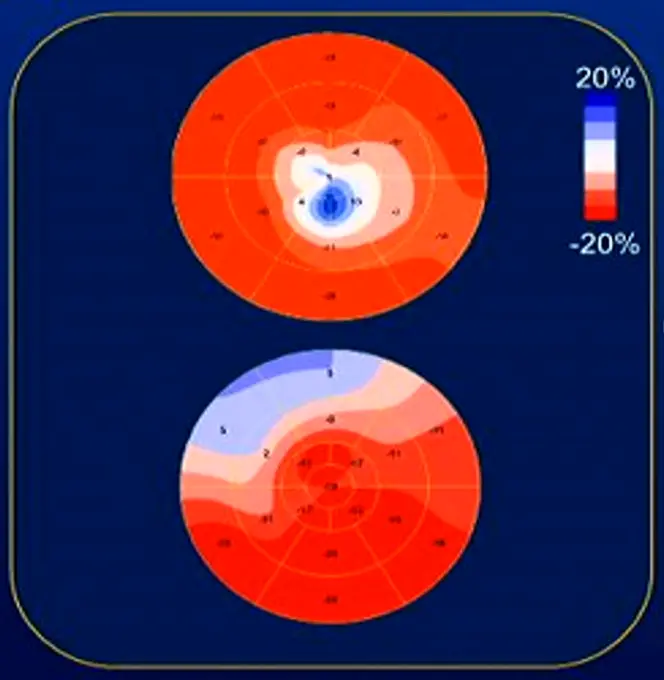

Strain Imaging

- The bottom shows strain in the septum

- The top figure shows strain with apical HCM

Apical HCM

- “spade-shaped” hypertrophy at the apex

- Recall, this is a risk factor for SCD

Acceleration of flow → Absence of flow → Flow again, aka “lobster claw”

Acceleration of flow → Absence of flow → Flow again, aka “lobster claw”

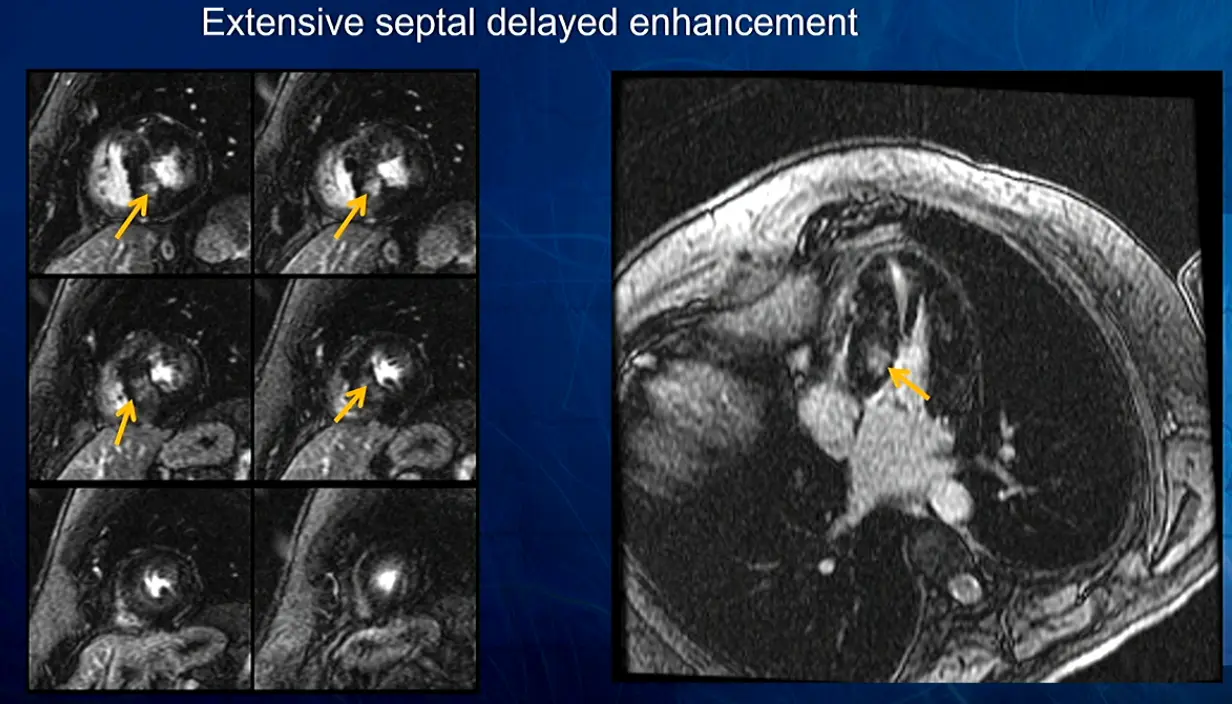

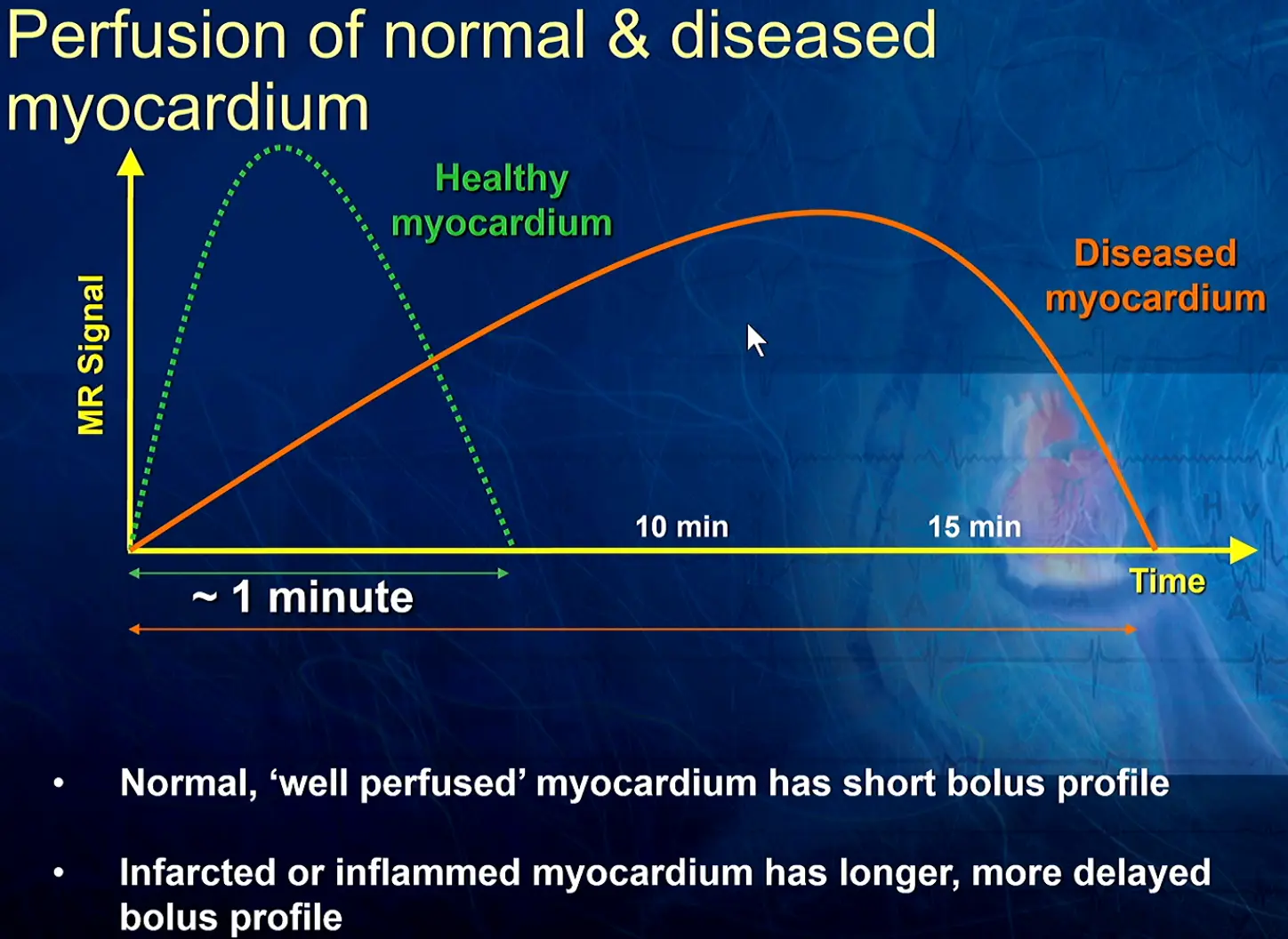

Cardiac MRI in HCM

Offers superior image quality compared to echocardiography and can be crucial in confirming the diagnosis, especially in cases of challenging echocardiographic windows. CMR can also detect myocardial fibrosis, a prognostic indicator in HCM.

In this example, patchy had patchy delayed enhancement suggestive of myocardial fibrosis. Fibrosis is expanding the ECV. Collagen is avidly attracted to gadolinium and holds onto it.

In this example, patchy had patchy delayed enhancement suggestive of myocardial fibrosis. Fibrosis is expanding the ECV. Collagen is avidly attracted to gadolinium and holds onto it.

Late Gadolinium Enhancement

- Extensive delayed enhancement is a minor risk factor increasing in importance

- Helpful for resolving difficult AICD decisions when major risk factors are inconclusive

- If LGE ≥ 15%, then may be an AICD candidate

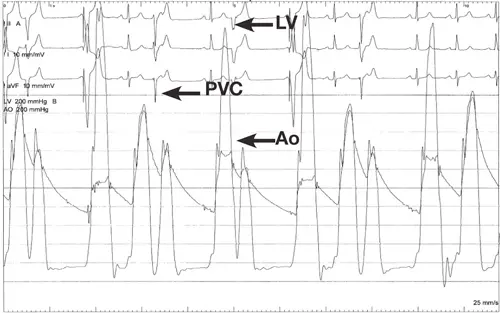

Invasive Hemodynamics

- Brockengrough-Braunwald-Morrow Sign 3

- Can be elicited in patients about to undergo alcohol septal ablation, TAVR, etc. to accurately determine the degree of left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction

-

- In the case study presented in 3, they describe a classic situation where the patient had no gradient at rest, but the beat after a PVC showed a marked gradient. This finding indicates the presence of LVOT obstruction with the distinct “spike and dome” waveform pattern.

- “After a PVC, there is a compensatory pause that causes an increase in diastolic filling time and ∴ an increase in diastolic volume. The normal physiologic response to increased stretch according to Frank Starling’s Law is to increase stroke volume by an increase in contractility, causing the arterial pulse pressure to rise. In patients with HOCM, the increase in contractility after a PVC worsens the LVOT obstruction, causing a decrease in the arterial pulse pressure and the Brockenbrough-Braunwald-Morrow sign.” 3

- In the case study presented in 3, they describe a classic situation where the patient had no gradient at rest, but the beat after a PVC showed a marked gradient. This finding indicates the presence of LVOT obstruction with the distinct “spike and dome” waveform pattern.

- “After a PVC, there is a compensatory pause that causes an increase in diastolic filling time and ∴ an increase in diastolic volume. The normal physiologic response to increased stretch according to Frank Starling’s Law is to increase stroke volume by an increase in contractility, causing the arterial pulse pressure to rise. In patients with HOCM, the increase in contractility after a PVC worsens the LVOT obstruction, causing a decrease in the arterial pulse pressure and the Brockenbrough-Braunwald-Morrow sign.” 3

Management

The 4 Ps of HCM Management

Prevent Symptoms, Prevent Strokes, Prevent Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) in the patient, and Prevent SCD in the family.

Managing HCM involves addressing four key areas:

- Symptom Prevention

- ⚠️ Decreases in preload, decreases in afterload, and increases in contractility promote obstruction.

- ∴ advise patients to avoid strenuous exercise, dehydration, alcohol, and stimulants.

- The postprandial state is known to provoke dynamic obstruction and may be employed clinically to unmask latent obstruction.2

- Eating → mesenteric vasodilation → ↓ peripheral vascular resistance, augmenting stroke volume akin to use of an arterial vasodilators; compensatory ↑ HR and mesenteric pooling of blood (↓ preload), resulting in ↓ stroke volume, further worsening dynamic LVOT obstruction.

- ⚠️ Decreases in preload, decreases in afterload, and increases in contractility promote obstruction.

- Medications:

- Beta-blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers reduce heart rate and contractility, easing LVOT obstruction.

- Disopyramide can also be used for its negative inotropic effects.

- ⚠️ Avoid vasodilators and digoxin, which worsen obstruction.

- Interventions

- Surgical Myectomy: Removes part of the thickened septum, relieving obstruction. Considered for patients with severe symptoms refractory to medical therapy.

- Alcohol Septal Ablation: Injects alcohol into a septal artery, causing controlled infarction and shrinking the septum. An alternative to surgery.

- Stroke Prevention:

- Patients with atrial fibrillation or flutter require anticoagulation regardless of their CHA2DS2-VASc score.

- Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) Prevention in the Patient:

- Risk stratification involves considering factors like family history of SCD, syncope, LV wall thickness, and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are recommended for high-risk individuals.

- SCD Prevention in Family Members:

- First-degree relatives of HCM patients require screening (genetic testing if the mutation is known, otherwise echocardiograms).

Pharmacotherapy 💊

Mavacamten

- Negative inotrope that ↓ LVOT gradients in HCM with LVOT obstruction

- TTE at weeks 4, 8, and 12 after initiation of therapy, then every 12 weeks for for gradient monitoring and to assess for LV systolic dysfunction, as part of the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program for mavacamten.2

ICD for SCD Prevention

- One of the major treatment initiatives responsible for lowering the mortality rate has been the evolution of sudden cardiac death (SCD) risk stratification strategies based on several major noninvasive risk markers that can identify adult patients with HCM at greatest risk for sudden death who are then candidates for implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) placement. 1

Interventions

Surgical Myectomy

Alcohol Septal Ablation

Footnotes

-

Ommen SR, Ho CY, Asif IM, Balaji S, Burke MA, Day SM, Dearani JA, Epps KC, Evanovich L, Ferrari VA, Joglar JA, Khan SS, Kim JJ, Kittleson MM, Krittanawong C, Martinez MW, Mital S, Naidu SS, Saberi S, Semsarian C, Times S, Waldman CB; Peer Review Committee Members. 2024 AHA/ACC/AMSSM/HRS/PACES/SCMR Guideline for the Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024 Jun 4;149(23):e1239-e1311. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001250. Epub 2024 May 8. Erratum in: Circulation. 2024 Aug 20;150(8):e198. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001277. PMID: 38718139. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

Abbasi M, Ong KC, Newman DB, Dearani JA, Schaff HV, Geske JB. Obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: many faces. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2024;37(6):613-625. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2024.02.010 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15 ↩16 ↩17 ↩18

-

Trevino, A. R., & Buergler, J. (2014). The Brockenbrough – Braunwald – Morrow Sign. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal, 10(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.14797/mdcj-10-1-34 ↩ ↩2 ↩3